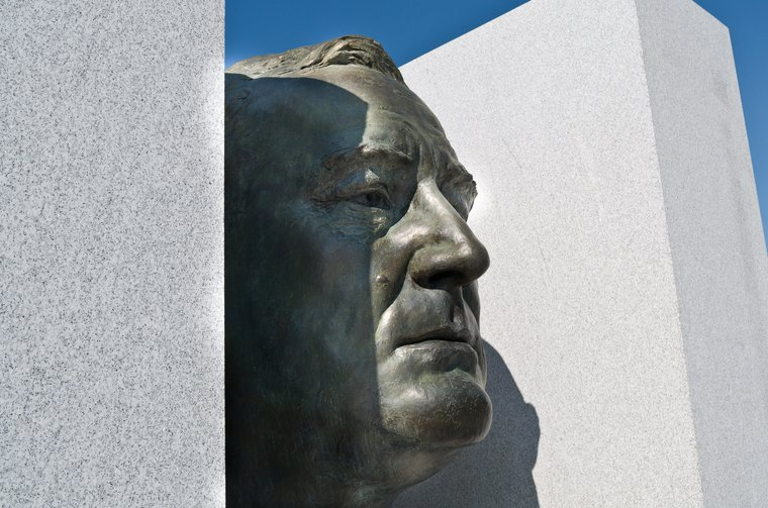

January 2021 marks the 80th anniversary of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous State of the Union Address, delivered by the US President in 1941 at a time of deep turmoil and conflict in the world. It also marks the beginning of a year in which we hope to ‘build back better’ after the torment of Covid-19. What principles should guide our response? Could they be based on the idea of freedom that motivated Roosevelt?

In his remarkable speech, Roosevelt spelled out his vision for a better world, premised on the notion of ‘four freedoms’:

“The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way – everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want, which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants – everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear, which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor – anywhere in the world.”

This part of Roosevelt’s speech became one of the foundations of the modern articulation of human rights and greatly influenced the text of the Atlantic Charter, the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

A code for living

Historians who have studied the genesis of this remarkable speech credit Roosevelt as the sole author of the four freedoms. Even though he had a number of speech writers who worked tirelessly in the days preceding his State of the Union Address, it was Roosevelt who dictated the writing of this particular section. The general belief is that Roosevelt was indeed the author of the four freedoms, with some scholars going so far as to call it an ‘American idea’.

This can, however, be convincingly challenged.

Anyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of the principles and texts that make up the theology of Hinduism and Buddhism will immediately point out that ‘freedoms’ are foundational constructs of the world view inherent in these religions. The difficulty we are presented with, of course, is that the essence of this thinking in Hinduism and Buddhism is spread across the many teachings that the world has inherited.

In a succinct and brilliant precis of the early thinking of Hinduism and of Buddha, a response to a call for ideas for the drafting of the UDHR in 1947, the eminent Indian political scientist Professor S.V. Puntambaker writes:

“They have propounded a code, as it were, of ten essential human freedoms and controls or virtues necessary for good life. They are not only basic but more comprehensive in their scope than those mentioned by any other modern thinker. They emphasise five freedoms or social assurances and five individual possessions or virtues.

The five social freedoms are (1) freedom from violence (Ahimsa), (2) Freedom from want (Asteya), (3) freedom from exploitation (Aprigraha), (4) freedom from violation or dishonour (Avyabhichara) and (5) freedom from early death and disease (Armitatva and Aregya).

The five individual possessions or virtues are (1) absence of intolerance (Akrodha), (2) Compassion or fellow feeling (Bhutadaya, Adreha) (3) Knowledge (Jnana, Vidya), (4) freedom of thought and conscience (Satya, Sunrta) and (5) freedom from fear and frustration or despair (Pravrtti, Abhaya, Dhrti).”

In this light, we can see that Roosevelt chose only some of the ‘freedoms’ from the long list available to scholars of Hinduism and Buddhism. Whether they were a direct influence on Roosevelt himself is not known. But we do know that he was influenced by the actions and writings of Mahatma Gandhi, who lived his life using the principles enunciated in the ancient Hindu and Buddhist texts.

In a similar vein to Roosevelt, but at an earlier time, Mahatma Gandhi also channelled these learnings into his vision of multilateralism: balancing the sovereignty of nations with the necessity of a global organisation; the need to build a peaceful world based on respect for non-violence; the universality of human rights; the necessity of disarmament, and so on. In this context, Mahatma Gandhi’s thoughts and writings significantly influenced the ‘rights and duties’ Article 29 of the UDHR.

In fact, the lessons from Puntambaker’s summary of freedoms are much deeper than what Roosevelt propounded. ‘Freedoms’ in Hinduism and Buddhism are derived from a basic principle of living that sees human rights and responsibilities as inseparable. This was also noted by Puntambaker:

“Human freedoms require as counterparts human virtues or controls. To think in terms of freedoms without corresponding virtues would lead to a lopsided view of life and a stagnation or even a deterioration of personality, and also to chaos and conflicts in society.”

A world to heal

Faced as we are with the twin global crises of the pandemic and climate change, we need to revive the remarkable wisdom inherent in the notions of freedoms balanced with responsibilities. The very principles of ‘duties done’ and then ‘rights acquired’ that dictated the life of Mahatma Gandhi and is at the core of thinking in Hinduism and Buddhism is what is glaringly missing in the limited conception of ‘freedoms’ articulated by Roosevelt and apparent in the manner in which Western societies have functioned. This is, of course, not to take away the major contribution that Roosevelt made by reminding the world of this civilizational thinking.

The timing in 1941 of Roosevelt’s four freedoms speech was perfect. The world was floundering as a result of global warfare, the great dislocation of people and communities, and the beginning of severe economic hardship. Principled leadership and the vision for a just world was sorely needed. Today, we are again at a global inflection point where the threats are not so different, given the scale of tragedy from the Covid-19 pandemic, and the impending destruction of humanity and the environment from climate change.

The protests, across Europe and the United States, against the restrictions necessitated by Covid-19 and indeed the assault on the US Capitol on January 6 to protest the carriage of democracy, are examples of ‘freedoms’ shorn of ‘duties and responsibilities’ on both an individual and collective level. It is these very countries and populations whose wealth and lifestyles have, in fact, been the major contributors to global warming that have brought our planet to the current ecological precipice. Contrast this, as an example, with the response to Covid-19 in the countries of South East Asia where a much deeper notion of duties and responsibilities has ensured a much more successful response to Covid-19 than we see in Western countries.

We need to recall, learn from and propound the remarkable wisdom inherent in the notion of freedoms and virtues flowing from some of the world’s great religions and eminent thinkers. As we prepare for the long road ahead we need to build, perhaps anew, a world where the realisation of human rights is paramount, tempered by the responsibilities we all have to each other and to our fragile planet.

Teaser Image: Phil Roeder, CC by 2.0