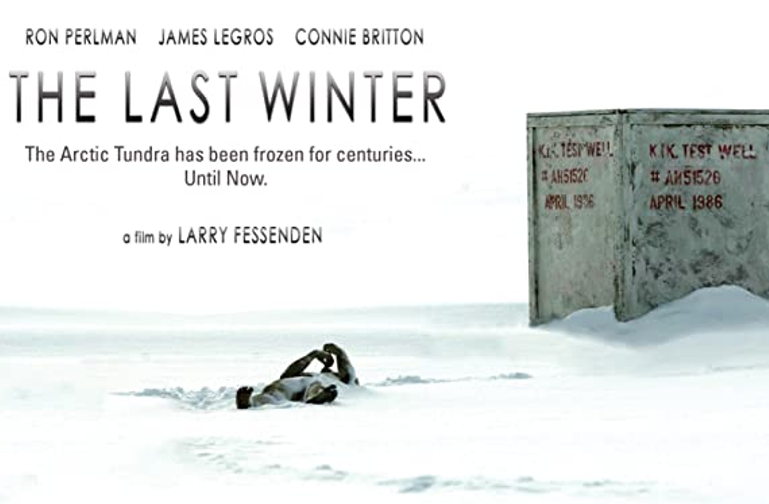

Directed by Larry Fessenden; written by Larry Fessenden and Robert Leaver; cinematographed by G. Magni Agustsson; edited by Larry Fessenden; music by Mark Ambrosino and Jeff Grace; production design by Halfdan Pedersen; produced by Larry Fessenden and Jeffrey Levy-Hinte. Released in Sept. 2006 by Glass Eye Pix, Zik Zak Filmworks and Antidote Films. Running time: 101 minutes. Rated NR

Starring: Ron Perlman as Ed Pollack, James LeGros as James Hoffman, Connie Britton as Abby Sellers, Zach Gilford as Maxwell McKinder, Kevin Corrigan as Motor, Jamie Harrold as Elliot Jenkins, Pato Hoffmann as Lee Means and Joanne Shenandoah as Dawn Russell

The Last Winter is an eco-supernatural horror film about oil workers in the Arctic who are stalked by a vengeful spirit determined to keep them from exploiting the oil. Despite this promising premise, the movie has big problems, including characters that are either undeveloped or one-dimensional, a disappointing adversary and a script that needlessly repeats information. While the film does have bright spots—including great location photography and echoes of the seminal excursion into Arctic horror cinema, 1951’s The Thing From Another World—these hardly merit its inclusion on your Halloween queue of spooky environmentally themed movies.

The setting is a tiny station inhabited by employees of the oil company North Industries, along with a team of environmentalists tasked with keeping the company in line with its environmental obligations. Base leader Ed Pollack (Ron Perlman) is the movie’s glib, domineering oil industry spokesperson and climate skeptic. Perlman, a fine actor, does the best he can with this one-note role. James LeGros functions as Perlman’s foil, lead environmentalist James Hoffman. He decries the destruction this operation is sure to bring and correctly points out that it’s unlikely to do much for America’s energy security anyway, telling Pollack, “The amount of oil that they’re gonna’ get out of here, they could save by inflating their tires and caulking their windows.” The remaining characters are so faintly drawn that it’s hard to get excited enough to want to say anything about them

Though Hoffman is on-point throughout most of the film, he does make one slightly irritating gaffe: his statement that he’s been sent to the Arctic to intervene on behalf of “the last pristine, untouched wilderness on the planet.” Even at the time this movie was made, the Arctic was, of course, no such thing; nor was there any place on Earth, period, still untouched by human activity.

Early into the plot, it becomes clear that something is amiss with the local climate. The temperature is rapidly rising to the point where Pollack is hard pressed to figure out how to move in all the heavy equipment they’ll need. It’s too warm to build ice roads, so Pollack proposes they transport the equipment on Rolligons (giant tires capable of moving easily over snow), despite the high cost of this option. Hoffman is vehemently against this because of the damage it would do to tundra at these higher temperatures. However, this point becomes moot when it grows too warm even for Rolligons. It then dawns on Hoffman that this entire region is caught in a climate feedback loop. Melting permafrost is releasing vast quantities of methane, which in turn is accelerating the warming by joining the atmosphere and adding to the greenhouse effect.

The film’s first suggestion of the paranormal comes when one character ponders the possibility that, just as fever is the body’s way of fighting off infection, so Earth may be raising her temperature as a way of flushing out the humans running roughshod over her biosphere. “Why wouldn’t the wilderness fight us, like any organism would fend off a virus?” he asks. This is hardly an original thought, but it’s an effective bit of foreshadowing. And it’s spoken over the backdrop of a bubbling, oozing crude oil seep that looks as menacing in its way as the blood that rushes down the halls of the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 horror classic The Shining, or for that matter, the seething river of slime that flows beneath Manhattan in Ghostbusters 2.

The weather isn’t the only thing going haywire; the human characters are also showing signs of instability. One marches naked in a trance toward one of the film’s key landmarks, a long-abandoned test well rumored to be haunted (and consistently shot so as to resemble a gravestone). A huge mass of hoof prints appears in the snow with no visible source. The station’s mechanic starts disassembling the engine of one of their vehicles for no apparent reason. Most disturbing of all, people begin catching blurred, dimly lit glimpses of some sort of nightmarish creature.

Hoffman initially attributes these strange goings-on to delusions brought about by sour gas poisoning. Sour gas is natural gas that contains high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide, making it deadly poisonous and prone to causing neurological dysfunction. From the telltale stench surrounding the station, it’s clear that this gas is present. Hoffman insists that everyone hightail it out of the Arctic posthaste. But between their suddenly malfunctioning communications equipment and Pollack’s refusal to deviate from their plans and thereby miss the drilling season, they’re slow to leave. In the meantime, people start turning up dead.

An alternative explanation for the mayhem comes courtesy of one of the film’s two Native American characters, Dawn (Joanne Shenandoah). During a conversation with Lee (Pato Hoffmann), the other Native American character, she mentions the possibility that they could be dealing with a figure from Indigenous myth known as the wendigo, which is often depicted as a wind spirit. But Lee is the hard-headed sceptic of the two, telling Dawn, “I believe what I see with my own eyes.” You can tell that the movie is going for a kind of X-Files dynamic between these two—with Lee being Dana Scully to Dawn’s Fox Mulder—but it’s barely pursued.

The film does two things right in unveiling its threat: It refrains from showing it too early, and avoids showing it too often. At first all we see are eerie distortions of the wind and forces exerted on objects by some invisible presence. This tactic of holding back the monster works because it fills us with a fear of the unknown.

If the movie had gone the Blair Witch Project route and never actually revealed its paranormal entity, it would have been far more effective. Either that or it needed to supply a more compelling creature than the one it does eventually give us, which looks like a cross between every monster you’ve ever seen out of a Hollywood effects shop and something from Disney’s Haunted Mansion. This thing is inadvertently hokey, not frightening.

But those windswept Arctic vistas sure look splendid.