Wanjiku Mwangi pours out the golden liquid onto her finger checking the flow and the colour. She puts some on her tongue, tastes and smacks her lips. “Yes, this is good honey,” she says.

Wanjiku is a co-founder and director of Porini Association. She has been integrating her spiritual path with reviving traditional nature wisdom in Kenya ever since she was introduced to the spirituality of nature through an immersion programme in Botswana in 2004. Over the years Porini has hosted dialogues on indigenous environmental knowledge and laws with communities in Kenya, mapped cultural landscapes, and is now connecting bee custodians along a honey trail that runs from central Kenya to southern Ethiopia.

I sat down with Wanjiku to talk about her path and how this latest project both ensures thriving communities and a thriving environment through bees and honey.

How did you come to this work?

I had worked for government, private sector, and consultancies in Kenya, Tanzania and the UK when I was invited to the Botswana Process. That’s where the story of trying to connect with nature and questing for what African spirituality and what the spirituality in nature is really started. That brought me back to looking at my ancestral lineage and connecting with that. After the process, I and other Kenyans co-founded Porini Association and began to look for communities in Kenya that were still steeped in their indigenous knowledge and connected to nature to continue the dialogues we had begun in Botswana.

How did these dialogues go?

We had numerous dialogues with communities. But we faced a lot of resistance because what communities wanted was money in their pockets. They said “You people are always coming to talk, talk, talk but we want to see where we can do something and get money.” So that niggled me for a long time. And I could see that yes, money is important. That’s how we live today. But how is it that we could get the money and still respect nature?

How did you deal with this challenge?

My answer came rather fortuitously as I held a ritual to bless a piece of land I had bought and one of the elders present gifted me hives.

Audio: Ole Supuko, an elder’s advice on the importance of the bee

When we had our first harvest I was really touched to see how much honey the bees had been making while I was just mucking about. That really hit me. So I started the quest to understand bees. And it’s at that point that I saw the question that the communities had been asking about money or prosperity come into play. Honey can give you money. But what I really wanted to stress is that the bees actually point towards nature more than we imagine. Once you start watching the bees and you connect with your bees, you see and learn the different plants they’re going to and which water they’re drinking. So I started connecting with the bees and with time designed the current flag-bearing project for Porini which is An African Honey Trail.

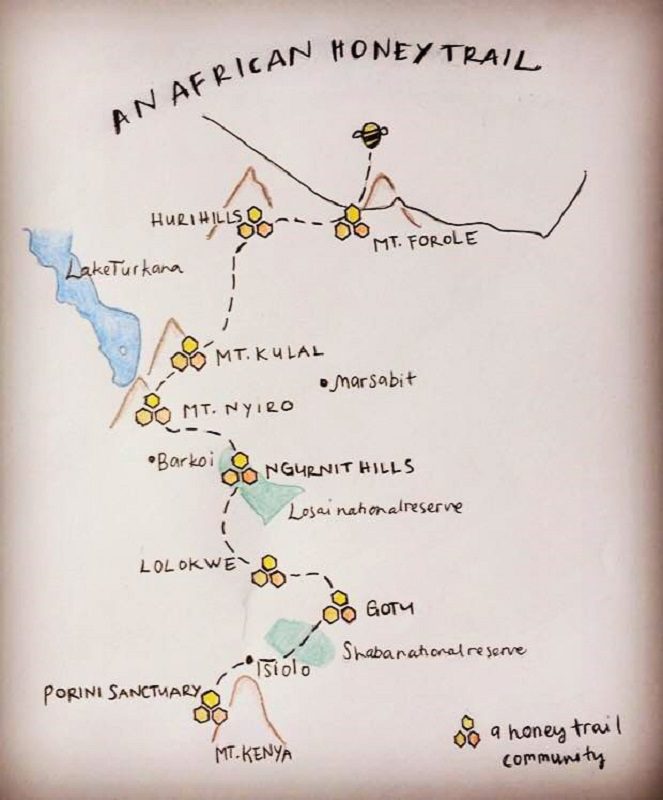

Tell me about An African Honey Trail

I wanted to connect as many ‘honey peoples’ as possible because I felt that they had been forgotten. The ‘bee custodians’, as I like to call them as opposed to beekeepers, had held the space for bees throughout our previous generations. And yet the hunter-gatherer is pitched at the bottom of the strata of livelihoods. Actually they need to be at the top, because without bees the farmer will not have any pollination, the pastoralists will not have wild herbs growing, and even for the fisher-folk, the trees next to the river give flowers that the fish use to rear their young. It dawned on me that there was much need to bring them out of the woodwork and at the same time invite more people to become keepers of the bee.

At the same time I knew that the bees would drive people to be more careful about their ecosystems and their immediate environments because they have to think about what the bees are eating, so they would start to safeguard their environments. So hopefully the project will bring the two together. If somebody raises the question of money it’s there. If you raise the question of the ecosystem it’s there.

You distinguish between bee custodians and beekeepers. Could you tell me about the difference?

An elder, Ole Sikoi, told me, “Don’t go bragging that you have bees, because you don’t own the bees. The bees own you, they choose you. So if they’ve chosen you, you’re very fortunate. And the bees will make you prosperous because they will guide you and show you, and they will make your environment much richer.”

I realised that in all the material I was reading the emphasis tended to be really skewed: have beehives so you can get money, so you can pay your kids’ school-fees, buy a cow, or pay your medical bills. I relegate the word beekeeper to people who only think about the bee for commercial purposes.

You can’t just look at it as the bees making the honey for you to make money because we’re actually robbing the bee of its honey. You’ve got to respect that so that when you harvest, you don’t harvest all the honey. Or in the drought you help the bees with some clean water.

I use bee custodians to distinguish that it’s not all about the money. And the reward from the bee is to allow you to take some of the honey and cash it so that hopefully you can grow the bee some more flowers. So bee custodians is what I’m for. I champion that very much.

African Honey Trail sketchmap. Map by Hanna Söderström.

How does the trail function?

We go into communities and find the bee custodians, engage with them, build trust and begin dialogues.

We’ve devised a system to track the ecological calendar. Most of the custodians actually have the calendars in their minds. They know at this time, this acacia is going to bloom. If there’s an impending drought they know so they store their honey. We thought we should start to record these ecological calendars so that new people wanting to get into bee custodianship would begin to see it. To be able to relate to your bees, you need to be in touch with the cycles of nature. You must follow the ecological calendar.

We’ve given out digital cameras for people to photograph flowers so that we can align the naming. We can figure out the botanical names and get to understand names cross-culturally.

We also encourage the custodians to keep diaries. And we say it’s for them really to get back into the pattern of reading the ecology, it’s not to report back.

Then we have quarterly gatherings and people trade their stories. And as we do this, we are collecting indigenous knowledge stories that have been around for years. We want to uplift this because indigenous knowledge has a deeper connection to the bee and to the ecosystem yet the modern bee keeper thinks that modern science is more important and traditional knowledge is not important.

I am also planning to have a beehive stop at the beginning of the trail where we can have an exhibition running, a museum, and then a shop that will sell the honey and other bee products. Honey is such a sacred thing that you don’t want to imagine that it’s going to be adulterated as some middlemen do.

This is also thinking about sustainability because grants are not sustainable. Once you don’t have the grant there’s nothing going on so one has to think about how to get money in a decent way that ploughs back in to the work and especially into the ecosystems which is where it begins.

At this beehive stop we hope to also have a place where we can start to engage children because children are very open and they will always remember. They keep the knowledge and it influences the way they think in the future.

You’ve mentioned as challenges funding coming into Porini; money for communities; people not seeing indigenous knowledge as important; ignorance about the bee and prejudice of people preferring modern technology over indigenous hives. What are some of the ways you confront these challenges?

Well, ultimately I think we are on the path regardless. Because when you look at the indigenous people they never received any funding but they keep at it because that’s their livelihood, that’s their path. So we continue.

What are some triumphs along the way?

Along the honey trail we’ve had rituals in each one of the stops, and the bees have come and occupied the hives so that’s been really good.

The enthusiasm of the younger generation has been overwhelming because I didn’t think they would find it cool enough to get into bees. Hopefully in that coolness and in that engagement they will start to safeguard the environment.

The hives we’ve installed have been well received and appreciated and some communities have gone ahead and installed more of their own. The realisation that they had forgotten about the bee for me was quite a bit of an achievement. For example, when a chief in Mount Forole at the end of our dialogues said that they would now start including the bee in their traditional prayers in which they pray about the rain, the children, the livestock, etc.

smoking hives for installation. Image thanks to Porini Association

How do you take care of yourself while doing this work?

There’s always turmoil because I’m trying to hold my path on deepening my spirituality, running an organisation, being the family member that I am, and trying to balance my friendships and other relationships.

The sanctuary I built on this land is where I come and reflect, heal and recharge.

It’s amazing how quick we are to charge our phones, we carry power banks and the minute you walk into a restaurant you’re looking for Wi-Fi and battery outlets but we’re not as quick to recharge our own batteries. It’s a really important thing, and sometimes I have to stop and say – just like the phone goes off and you have to stop and charge it so you also have to stop and recharge your batteries, otherwise you could just fizzle out.

For me nature is where I go for the battery outlet, it’s where I go for the Wi-Fi. It’s where I connect and recharge and then I can pick up another day and start.

What’s your vision for the future of this work, and for Africa’s environment?

In Kenya I want to see a million hives go up. And if each country would adopt a philosophy or a policy to have more hives, the better. Give the bees more homes because at the moment there’s not enough old trees for them to hive in in the forests and our forests are dwindling.

The more people who have hives the more people will say “Oh no, don’t cut that tree. We must plant these flowers for the bees.” So catalysing more hives catalyses more safeguarding of the ecosystem. If more people got on board I think the world would certainly become a better place.

To really get the respect of the bee back and people in the frame of mind where when they see a bee they say “oh wow, wonderful, the crops are going to be pollinated”, or “wonderful, there’s going to be more honey”, not “oh wow I’m going to get bitten”. That’s really my big dream.

Ethiopian hives in tree. Image thanks to Porini Association