Branko Milanovic has written a response to my argument. As I read it, I was struck by two things – both quite significant.

First, Branko now seems to accept the science on how “green growth” is not a thing, and has backed off his assumption that endless growth is (a) possible, and (b) something we should promote. Or at least he has chosen not to defend his earlier claims on this matter. This is quite a shift.

Second, Branko does not insist that growth is necessary in rich nations. In fact, he seems to agree that we can maintain well-being in rich nations while reducing material consumption. And he accepts the notion that we can accomplish this by shifting to a different kind of economy, along the lines of my suggestions. “I do not think that this program is illogical,” he says.

So far, then, we’re on the same page.

But Branko doubles down on one bit of his earlier argument: that degrowth is not politically feasible. “It is just so enormous, outside of anything that we normally can expect to implement, that it verges, I am afraid, on absurdity,” he writes. He claims that people are so penetrated by the ideology of competitive consumerism that they would never voluntarily walk away from the system. So it will be impossible to put degrowth into practice in a democracy.

I do not disagree with Branko that the task is enormous; I have complete empathy with this perspective. Indeed, it is the single greatest problem of our century – how to enable human flourishing while reducing emissions and material throughput – and it demands our total focus. But let me offer three thoughts that give me hope.

1. People are not just consumption bots.

Branko advances a dystopic vision of people who identify totally with the extrinsic values of competitive consumerism and growth.

First, it’s just not true. People over-consume not because it aligns with their inner values, but because they feel compelled to do so, and because our economy is structured so as to incentivize it. The system requires endlessly growing consumption, and so externalizes true costs and bombards us with messages and ads to provoke consumptive behavior, seeding us with discontent and anxiety that is particularly acute in conditions of high inequality.

It will be difficult to overcome these forces, to be sure. We need to change the messages, change the incentives, internalize costs, and ultimately change the logic of the economy itself. But we have on our side the fact that people already yearn for something different. According to recent consumer research, 70% of people in middle- and high-income countries believe overconsumption is putting our planet and society at risk. A similar majority also believe we should strive to buy and own less, and that doing so would not compromise our happiness.

This is not surprising. Nobody wants to live in an economy that is so obviously programmed to ruin the planet we call home. It makes us feel horrible.

Importantly, there is a massive literature in happiness economics, anthropology and social psychology that finds that people have much more nuanced visions of the good life than the old homo economicus model would suggest: that they aspire to good health, intimate relationships, community, knowledge, and time, and are motivated by autonomy, mastery and purpose rather than monetary reward. We need only appeal to the better angels of our nature.

As for growth, check this out: 81% of people in Britain believe that the government’s prime objective should be “the greatest happiness” instead of “the greatest wealth.” This throws a wrench in Branko’s argument. And it brings me to my next point:

2. Democracy is the answer.

Branko articulates a common worry: that the only way to degrow an economy is to have some kind of authoritarian dictatorship do it for us.

I completely disagree. Imagine: what if we had an open, democratic conversation about what kind of economy we really want? What would the economy look like? What kinds of objectives would it have? How would it distribute resources? The evidence I’ve cited above leads me to believe it wouldn’t be anything like our current system, with its tyrannical obsession with endless GDP growth and pro-rich resource distribution.

We have never had this conversation on a mass scale, because (a) our media is controlled by a small number of mega-corporations that are structurally disinclined to facilitate such a conversation; and (b) we do not live in real democracies. As a recent study pointed out, the United States resembles an oligarchy with the policy preferences of elites routinely overriding those of the majority. The same is likely true in every nation where money buys political outcomes.

So, as George Monbiot put it in an elegant proposal on Viewsnight recently, kick big money out of politics, dismantle the media conglomerates, and let’s have a real discussion about the economy. Our vision of a different economy does not require totalitarianism. Quite the opposite: it requires the exercise of democracy against the violent tyranny of growth.

3. There is already a movement for change.

Branko concludes on a frustrated note, saying, basically: “if you really believe in degrowth, then why don’t you try to make it happen?” He assumes that we are crying out in the wilderness, and that nobody will actually accept what we propose.

I’m not so pessimistic. But let me be clear: is there widespread public support for de-growth? Not yet. And that’s hardly surprising: as I have been at pains to point out, degrowth is structurally impossible in our existing economy. So the first step is to change the logic of the economy. And on this front the movement is surging.

The US states of Vermont and Maryland have already adopted an alternative to GDP – the Genuine Progress Indicator – and a number of European governments are considering the same. Key economists like Stiglitz and Sen support this shift, and it appears as a goal in the SDGs. As for decommoditizing social goods, there is overwhelming popular support for this in most rich nations. About debt: there is the Jubilee campaign, and the anti-debt movement among US students, and virtually everyone in Greece. And on fractional reserve banking there is Positive Money, and the Chicago Plan promoted in a recent IMF report.

A carbon tax would be a key step – something that Branko himself supports, along with a growing chorus of others, as a way of internalizing costs. I bet getting rid of the $5.3 trillion fossil fuel subsidy would be popular too (look at the divestment movement for proof of mass resistance to fossil fuels). As for redistribution as a substitute for growth: is there momentum there? Just look at Occupy, the Bernie campaign, the Corbyn Labour Party – or talk to any person on the street.

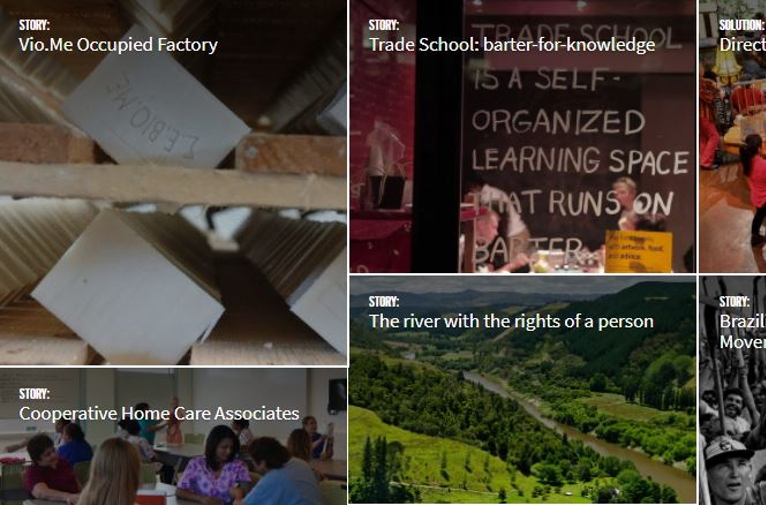

Speaking of Labour, Dr Dan O’Neill, a prominent degrowth economist, was invited to write a policy brief that the Labour Party has publicized, highlighting a number of sensible objectives, including limits on resource use and waste production, and a shorter working week. These ideas were unthinkable even a decade ago. Now they are shooting into Europe’s biggest political party – and finding concrete expression all over the place, from the local food movement and Transition Towns to alternative currencies and regenerative farming.

This is just a small fraction of what’s out there. We are already building the new economy. Nearly everyone I meet is inspired by this – and students and young people rally around it with energy and passion. Still, we have a lot of work to do. I hope that Branko will join us.

* * *

Our demands are not “absurd”, as Branko claims. What is absurd is to believe we can continue with the status quo, against the rising tide (literally) of evidence to the contrary. Fortunately, we have one thing in our favor: while it may not be possible to change the laws of physics, it is possible to change social and economic systems – we have done it many times in the past, and we will do it again. We have to.

This brings me to another thought. In service of his bleak view of consumption bots, Branko recruits the image of Sudanese immigrants crammed into tiny compartments on trains so that they can make it to France and… “buy more stuff.”

I bet any actual migrant would object. As someone who has spent years living with migrants and researching migration, I know I do. They’re not risking their lives because they want to buy more stuff, but because they want to survive, and – if luck is on their side – live a decent life. Many risk the journey because they’ve been displaced by violent military intervention in the service of Western capital, or in order to flee the ravages of climate change in their home countries. It is coercion, not choice.

If we zoom out, it becomes clear that these refugees are in many cases victims of Western over-consumption and excess growth, not disciples of it. They are a living, breathing reason for why we need to change the system.

* * *

Let me finish by clarifying one key point. On a couple of occasions Branko has tweeted his dismay that we simultaneously call for degrowth while also calling for the end of austerity. But this is not a contradiction.

Think about it: the whole point of austerity is to slash public goods in order to re-start economic growth, with devastating consequences for the poor. Austerity is a violent expression of our system’s need for endless growth. In this sense, de-growth is the exact opposite of austerity. It calls for redistribution (in support of public goods, for example) in order to render growth unnecessary. It names the violence of the growth imperative and calls for something better.