As we celebrate the launch of Dark Mountain: Issue 12 (SANCTUM), now available from our online shop, we’ve asked the team behind this issue to introduce different aspects of the work that went into its making.

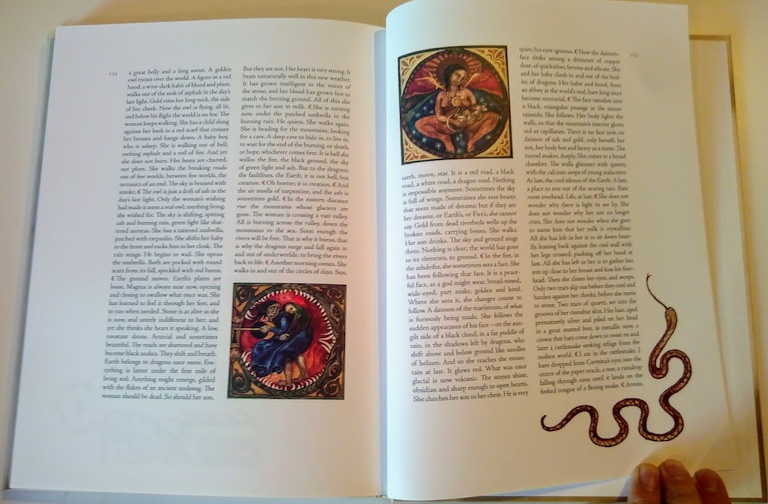

Following Thomas Keyes on the story of the artwork and Sylvia V. Linsteadt on the marginalia that runs through the book, today Dougald Hine introduces the twelve major pieces that form the spine of the book.

If your copy of our twelfth book has already landed, then you’ll know that we’ve shaken up the form of Dark Mountain in a whole lot of ways. Not least, where a typical issue would contain forty or more pieces ranging from short poems to longer essays or stories, this time around we have built the book around twelve longer texts – and having introduced the other elements of this issue, it seems like time to tell you a little more about these.

The book opens with Sara Jolena Wolcott standing at a bus stop in Queens, waiting for the Q100 to Rikers Island jail, on her first day as a trainee prison chaplain. In the darkness of the jail, where women are held in uncertainty, awaiting trial, Sara takes us behind the story of climate change as ‘the unintended consequences of the brilliance and ingenuity of white folks’, into the histories of race and displacement, the theft of land and the theft of bodies and the roots of ecocide in the Christianity of empire. It’s a story of her own family, the land she grew up on and the stories no-one ever told her about that land. And it’s a search for the grounds on which healing might begin.

‘Sometimes the still heart of things has to spin us a tale to draw us back in,’ murmurs Steve Wheeler in the opening lines of ‘The Fire in the Cave’. This is a spiralling story about mythic thinking that winds around continents and millennia. ‘The stories our ancestors left us are not solutions or explanations. They speak a language of dreams, pointing in silence to a cave we half-recognise, where ancient animals step out from the walls, lit by a light from a source we cannot see.’

The next piece, ‘Between Home and Hell’, opens with a troubled winter solstice, a gathering at which a collective yearning ‘to feel connected to something old and real’ falls against the brokenness of the culture in which we are living. From this starting point, James Nowak takes us into the history of the ‘corpse door’, a phenomenon known from Icelandic poetry and found in the architecture of old buildings across the Nordic countries. These physical thresholds provide a glimpse of what it might mean to be part of a culture that takes seriously the relationship between the living and the dead.

In ‘Roots and Branches’, Pelin Turgut describes leaving Turkey after the repression of the protests to save Gezi Park and the coup that saw friends and colleagues imprisoned. Struggling to root herself in London, she finds herself drawn to the city’s trees, and realises that she is not alone: ‘I found other exiles adrift in the many parks I got to know: a Palestinian man shaking mulberries off a tree with a stick; an eastern European grandmother snipping elder flowers; a Syrian family collecting damsons for jam.’ Together with a friend, she starts work on a film in which they seek out ‘The People Who Speak to Trees’, and through this journey she slowly finds a way of being at home in the country where she is now living.

Rob Percival’s work takes him to farms – and at the opening of ‘Pig Rhythm’, he is on his knees, face to face with a hog. A grotesque disregard for the rhythms of life runs through the practice of industrial farming and, with it, a blindness to the roles that other animals have played in shaping our own species. Telling stories of ‘man the hunter’, we miss the reality that our species spent much of its existence as prey. Our ancestors learned the sense of rhythm from imitation of the animals around them, dancing their movements and finding their shapes in the stars, and it is here that Percival traces the deep roots of the human sense of the sacred.

‘Ancient and modern societies were alike in at least one respect: disability happened, whether from birth or over the course of life.’ In ‘Cripples and Crooked Paths’, Craig ‘VI’ Slee reflects on the experience of being defined by difference and the long history of connections between the Otherness of physical disability and the Otherworld. His words are infused with a fierce defiance and the inrush of ecstatic inspiration that comes at strange moments, as time falls away among ruins on a Cumbrian hillside, or after hours of staring at the blank page. ‘Nowadays you would have been fine,’ he hears the myth of progress whisper. ‘To which I reply I am fine. I am crippled, and I am nowadays.’

Sayalay Anuttara was twenty-five when she entered the monastery of Pa Auk Tawya in Burma. For the next five years her life revolved around training in meditation which she has now taken with her into the world. It is a discipline that leads her to a suspicion towards talk of ‘the sacred’: ‘To be honest, I find the whole side of spirituality that says “this is a mystery, it is beyond our understanding” quite deeply annoying.’ In ‘The Bottom Line’, she discusses money (her previous training was as an economist) and the environment from the point of view of a Buddhist practice that is sceptical of received wisdom and committed to direct investigation.

Over recent centuries, writes John Michael Greer, the main religion of the West has been the worship of Man: ‘Like many another deity, He was born in a cave, slew fabulous beasts in His youth, and thereafter set out in pursuit of His divine destiny among the stars.’ In ‘Confronting the Cthulhucene’, Greer draws on the dark fantasies of H.P. Lovecraft to contemplate a future in which people will still be around, but the deity Man will be dead.

Michelle Ryan encounters the reality of her own death when the weather turns against her and her companions on a Himalayan pass. Having spent half a lifetime studying Sanskrit and Vedic philosophy and teaching yoga, she has finally made the journey to India which an early marriage and the responsibilities of parenthood prevented her from making in the 1970s. In ‘Kedarnath’, she tells the story of that journey and how it changed her.

‘Don’t think just because your dreads have finally grown out, you don’t pay taxes, you have all the dope you want and you grow miles of one big ugly kind of onion, of droopy giant mediocre-tasting carrots, or you’ve canned up a hundred jars of garlicky giant baseball tomatoes and turned piles of ball-and-chain cabbages into tons of kraut, that now you’re farming.’ Martín Prechtel’s ‘The Marriage Contract with the Wild’ is a call to reawaken a relationship which he tells us is common to indigenous cultures around the world – the kinship between humanity and wild nature which came about through the domestication of plants. We have forgotten how to honour this agreement, Prechtel writes, and the consequences are all around us.

Liz Slade is an atheist, trained in science communication and working with public health, who has come to the conclusion that a lot of babies were thrown out with the bathwater when we stopped going to church. ‘The God-Shaped Hole’ is the story of her experiences exploring new ways of building community among the ruins of traditional religion.

Finally, in the last of these twelve pieces, Dougald Hine traces the ways in which the sacred went underground during recent centuries and how this shaped the modern idea of the artist. In the words of the Dark Mountain manifesto, ‘Religion, that bag of myths and mysteries, birthplace of the theatre, was straightened out into a framework of universal laws and moral account-keeping.’ This essay is about where the myth and mystery went – and what this might tell us about the roles that art can play now, in the end-times of modernity, under the shadow of climate change.

And at that point, the voice in the margins sweeps in to claim the final pages of the book, as Sylvia V. Linsteadt and Rima Staines conjure their vision of the Sybil of Cumae, and this issue of Dark Mountain comes to a close.

SANCTUM BOOK LAUNCH

9TH DECEMBER

To mark the release of our twelfth book, we will be holding a day of workshops, followed by an evening of music, moving images and performance, at the beautiful Dartington Estate in Devon on 9th December.Afternoon workshops will be led by two Issue 12 editors, writer Steve Wheeler and artist Thomas Keyes, exploring the connections between art, ecology and spirituality. Later we will gather outside for a guided candlelit walk of strange encounters, unlikely inhabitants and moments of shadowed beauty. Finally we will be hosting an evening of shared food, drink and entertainment in the Upper Gatehouse, featuring readings from Issue 12, short talks from some of its contributors, live music and art, and moving images. To find out more about this event, and to book a place, see the ticket page here.

—

You can order a copy of Issue 12 from our online shop for £18.99 – or for a special rate of £9.99, if you take out a subscription to future issues of Dark Mountain.

—