The 2016 presidential election and the period following will undoubtedly be remembered as a watershed in American politics. It is too early to tell just how the election and its aftermath will be recalled by historians; its consequences are still unfurling and likely to continue doing so through the next presidential election cycle in 2020.

It is never too early, however, for the clean energy and climate defending communities to begin thinking seriously in terms of what comes next. Will the molds broken in 2016 be recast as they were, or will the anger, division and disgruntlement continue in 2020 and beyond?

Will the next nominees for president and Congress be consummate outsiders or will establishment politicians be re-established? Can either of the two major political parties be counted on to halt the damage done by Trump and company to the environment—to say nothing of reinstating needed protections and making up for the time already lost in transitioning to a low-carbon future?

Six months into his presidency, it is clear the chaos of the campaign has accompanied The Donald into the Oval Office. It is likely chaos will rule longer than Trump himself.

His first 200 days in office will be remembered not for what he did, but what he undid.

— Trump has not simply failed to drain the swamp; he’s added to it and stirred the muck up while he was at it. —

On the eve of Trump’s six-month anniversary in office, the White House released its first federal regulatory agenda and bragged a bit about its (un)accomplishments to-date. As reported:

…the Trump administration has taken to reduce “unnecessary” regulations. Agencies have withdrawn 469 actions that were propose by the Obama administration last fall and have reconsidered 391 active actions by reclassifying them as long term or inactive according to the agenda.

[Trump] “kept his campaign promise to coal miners” by rolling back the Stream Protection Rule. In early February, the House and Senate voted to repeal the rule using the Congressional Review Act. (emphasis added)

The specific action taken will depend upon the rule being acted upon. Major rules like the Clean Power Plan (CPP), the Clean Water Rule (WOTUS) and New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) for oil and gas drilling wells are likely to make it only part way through the reform process before being challenged in court. From then on it may take years before final decisions are made.Law suits have become the major go-to strategy for climate champions. The administration’s unimpressive regulatory win-loss ratio in the courts is—in a perverse way–good for the environment. Law suits as surrogates for policymaking not so much. Costly in terms of time and money, court challenges are hardly the dynamic means needed to protect nature and society from environmental harm.The judiciary was never intended to perform the role of policymaker. Federal courts are to: interpret not write laws; hear and decide actual cases and controversies; and, protect constitutional rights and freedoms. The skills needed to craft good policies, e.g. imagination and a willingness to think outside constricted boundaries, when exercised by a court of law impugns its integrity and diminishes its ability to perform as a credible check on executive and legislative authorities.— Today’s politics have pushed aside the concept of give and take, replacing it with a virulent and threatening either or-else ethos. —

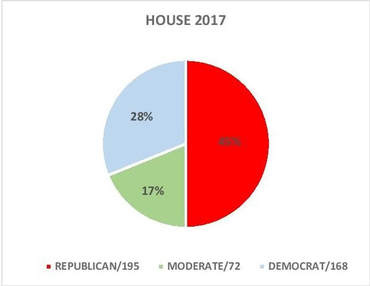

Over the past twenty years the Congressional divide has become deeper and wider almost to the point of being uncrossable. As shown in the two circle graphs the number of House members (shown in the legend) considered moderates by the non-partisan Cook Report has decreased by over half in the last twenty years.

Partisan-productivity: A 21st Century Oxymoron

The corresponding rise in partisan members of the lower chamber is reflected in what hasn’t gotten done in the same period. The last time Congress managed to enact all 12 appropriations bills by the start of the new fiscal year was 1996. Since then, most federal budgets came into force through a series of last-minute, white-knuckled Continuing Resolutions to avoid government-wide shutdowns.

Annually providing the funds and direction required to govern the nation is at the heart of Congressional responsibility. To put it bluntly, partisanship is a p**s poor way to run a railroad. Yet, the trend continues.

Executive and legislative policymakers show an alarming willingness to sacrifice the welfare of the nation in exchange for political dicta disconnected to the practical needs of the people. Why else would The Big D and his merry band of Congressional Republicans wish to enact a healthcare bill that leaves tens of millions of Americans in the lurch and supported by just 12 percent of voters?

To be fair the Democrats are no better. When did doctrinaire resistance to anything and everything the other political party suggests become all an opposition party stands for? Wait—I remember–when the roles were reversed.

Law suits of necessity will continue to be a major element of any strategy to combat climate change and to protect the health and welfare of the nation. Ultimately, however, legal challenges are defensive in nature. Like Continuing Budget Resolutions, they mostly maintain the status quo.

Can a law-suit be proactive, i.e. ordering a reluctant administration to issue regulations against their principles? Yes-but…even those instances are almost guaranteed not to be very productive.

Take, for example, a lawsuit requiring the Trump administration to reverse its rescission of the Clean Power Plan (CPP) and to regulate CO2 under the Clean Air Act (CAA), as interpreted by SCOTUS in Massachusetts v EPA and other established legal precedents. The principal plaintiff in the case of Earth v Trump[i] is joined by a host of others, e.g. environmental organizations, youths and states.

Three years after filing, SCOTUS affirms the plaintiffs’ contention and unqualifiedly orders the Trump administration to issue regulations limiting the amount of carbon emitted by both new and existing power plants. The EPA is told to set the new standard minimally no lower than what a prudent reading of the preponderance of scientific evidence would dictate.

Beyond Twitted rantings out of the White House, what happens next? Well, EPA:

- studies the problem by reviewing the scientific evidence alleging the climate is changing and humans bear much of the responsibility and asks its own—Trumpian Science Advisory Board what it thinks;

- issues ANPRMs and NPRMs;

- conducts hearings;

- prepares and publishes a Draft Rule in the Federal Register; and,

- finalizes the Trump Clean Power Plan (TCPP) as the standard of the land some three years after the SCOTUS ruling in Earth v Trump [i].

Game, set and match to the enviros.

Or, is it? Depending upon the standard(s) crafted, the Agency’s action could again be the subject to legal challenges.

The EPA during the Obama administration also drafted and issued a plan responsive to a court opinion. It was promptly challenged in court by 27 states and a couple of hundred other organizations and individuals. Plaintiffs in that case, including the State of Oklahoma represented by then Attorney General Scott Pruitt, charged the Agency with exceeding its authority.

Given Pruitt’s belief the EPA doesn’t have broad authority to regulate GHGs and Trump’s continually denying there is any problem, it is likely the regulations drafted by EPA in response to the high-court’s decision in Earth v Trump will be considered weak and wanting by the original plaintiffs in the case.

Back to court they go, where this second case will be found a legitimate controversy; the plaintiffs acknowledged to have standing having been harmed or potentially being harmed by the Agency’s proposed action; and, the federal court(s) recognized as the proper venue in which to resolve the issues. All three the necessary elements for the case to go forward.Three years after filing Earth v Trump 2, SCOTUS affirms the plaintiff’s contention and unqualifiedly orders the Trump administration to issue regulations limiting the amount of carbon emitted by both new and existing power plants. Finally, the case is decided.

Or is it…? I have just four words to say at this point: Groundhog Day, the movie!

To repeat, the courts were never intended to perform the role of policymaker. They are a poor substitute for a functioning political system.

Getting [the] U.S. out of partisan gridlock and back on the path to a sustainable future.

It is always possible the 2018 mid-term and/or the 2020 presidential elections may put into office a sufficient number of same-party partisans willing to protect the environment and actually able to govern.

The term govern here means to craft and to enact constructive legislation and to undertake and to complete the necessary implementation actions, e.g. new rules and budget allocation. The number of partisans sufficient to the task of governing likely means the need to capture both the House and Senate with disciplined majorities, as well as the White House with a disciplined occupant.

With the nation as evenly–some might add vehemently—divided as it is, the more realistic prognosis is the next elections will simply continue the partisan pattern of the last 20 or so years. It is easy to project the current Trump inspired chaos as a catalyst for future Democratic victories.

Easy, perhaps, but likely incorrect on two levels. First, there is not currently much evidence suggesting the Democratic Party is the choice of Republicans and independents opposed to Trump. Second, holding a majority of seats in Congress and the White House is no guarantee these days of actually being in power.

Certainly, Trump’s style, substance and lack of an appropriate moral compass is part of the problem. It is not, however THE problem. At the least, it is not an accurate assessment of what is preventing majority parties from being able to get much done while in office.

The extreme divisiveness of the electorate is itself reflected in the two major parties. Both the Republican and Democratic parties seem little more than convenient gathering places for various factions wanting access to established campaign machinery.

Factionalism [ii] within the Republican Party has certainly been a major factor in its failure to capitalize on majority status. Even with majorities and a president willing to sign almost anything a Republican Congress can manage to put before him, the “ruling party” has very little to show for their first 200 days in office. Congress, like the White House, has succeeded mostly in undoing things, e.g. Obama-era environmental regulations.

As for the Democrats, divisiveness is perhaps the major contributor to its current identity crisis. The Better Deal initiative recently announced by Senator Schumer is already being vilified by various factions within the party.

The House Freedom Caucus (HFC) has been largely responsible for much of the Republican’s inability to pass healthcare legislation. It has in the past caused closure of the federal government and promises do so again in 2017.

— Like them or hate them, but, nevertheless, learn from them. —

The problem of legislative gridlock and failed governance is not going to be solved anytime soon by routinely voting the out’s in and the in’ s out over the course of an election cycle or two–then rinsing and repeating.

The question we are left with is: what’s a practical alternative? Unfortunately, I don’t have a pat or complete answer.

I do, however, have a suggestion that the clean energy and climate defending communities might want to discuss amongst themselves.

The House Freedom Caucus’s 36 or so members have an outsized impact over their 399 Republican colleagues. In recent months, there have been other examples of how the few can influence—under certain circumstances—the actions of the many.

National elections in the UK and provincial voting in British Columbia have provided other instances of the power of small factions. Miscalculating the sentiment of British voters, Conservative Prime Minister May was forced to seek an arrangement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland. The Tories fell eight votes short of an outright majority.

The…anti-abortion pro-Brexit party of climate change deniers who don’t believe in LGBT rights, and who Theresa May now has propping up her failing government.

Strange bedfellows though they may be, both parties gain something through the arrangement. The Tories now control a majority of seats in Parliament, reducing the threat of Labour opposition. The DUP is accorded power much above their 10-seat stature.

The agreement is not a loyalty oath. For its part, the DUP agrees to support the government on all motions of confidence; and on the Queen’s speech; the Budget; finance bills; money bills, supply and appropriation legislation and estimates…the DUP also agrees to support the government on legislation pertaining to the UK’s exit from the EU and legislation pertaining to national security.

Interestingly the agreement does not extend to maintaining the current leadership of either party. Should the partners wish to change their leaders, they may do so without cancelling the contract.

A similar Confidence and Supply Agreement, between the British Columbia Green and New Democrat Caucuses, was signed after the Province’s recent elections. The agreement establishes the basis for which the BC Green Caucus will support a BC New Democrat Government. It is not intended to lay out the full program of a New Democrat Government, nor is it intended to presume BC Green Caucus support for initiatives not found within this agreement.

The BC Greens, with just 3 of the 87 seats in the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, managed to be the straw that toppled the BC Liberal Party from its 16-year majority position. The Greens and New Democrats share an extensive list of common goals in areas as far ranging as education, infrastructure investment, proportional representation, affordable housing and the minimum wage.

Environmental issues on which they agree include pipeline rights of way and carbon taxes. Josha MacNab, B.C. Director of the Pembina Institute said of the newly forged partnership:

We’re pleased that both the NDP and Greens promised to address B.C.’s rising carbon pollution and build a strong and resilient economy. Raising the level of ambition of climate action in B.C. is imperative for the province to secure economic prosperity, protect our families and communities, and do its part in reducing Canada’s carbon pollution…

Such rule from behind arrangements between major and minor political parties are not coalition governments in the traditional sense. They are limited rule-by-contract partnership agreements focusing on certain common interests and agendas, while leaving each of the parties free to attend to internal leadership matters and to act independently on issues outside the agreement.

Most of the governments in Western Europe operate with some type of coalition arrangements; and, nearly all have at one point or another, since World War II.

Would such arrangements be workable in the U.S.? Perhaps. In any event, it might be a good time to find out.

A U.S. Green (Lite) Party

Differences between the multi-party culture of European nations and the two-party system of the U.S. would have to be accounted for however. So, what might an American version of an agreement between a Green faction and a major party look like, and how would one go about establishing it?

To start, a discreet and organized Green (Lite) party or faction would need to be established. The exact nature of the party/faction could vary; minimally it must be an entity in control of its members and able to establish an independent identity.

It could be a legally incorporated entity or an informally agreed to arrangement of some sort, e.g. the HFC. As a legal entity, it would be permitted to solicit funds in a transparent manner.

Whether an informally established faction within the Democratic and/or Republican parties could be done would depend upon the party and the proposal. It is likely such an arrangement would prove problematic, as both the major parties would naturally be hesitant to share funds and legal/electoral standing with a group over which it had little control.

That’s not to say it would be impossible. After all Republicans continue to share power with the HFC and the Democrats have so far been willing to let Senators Sanders (VT) and King (ME) caucus with them.

(Paranthetically,, use of the existing Libertarian or Green Parties is not recommended. They carry too much baggage and have often nominated caricatures rather than viable candidates.)

— A U.S. Green (Lite) Party should not aspire to run a presidential candidate, focusing instead on becoming a legislative force to reckon with. —

Neither need it be in every state. Such organizational pressures in terms of time, money and recruitment sets an unrealistically high and unnecessary bar.

It is important to understand the nature of the role of a party-lite. It is a facile and disciplined unit of sufficient size that when brought to bear on behalf of its partner party tips the balance between losing and winning, primarily within legislative and public opinion venues.

A Green (Lite) Party, in most respects, is a junior member of a government-by-contract. Think of how the Tea Party came together and how it was able to impact the mainstream Republican Party acting in such a capacity.

How many Congressional seats would be needed is of course the issue. Given the recent experiences in the UK and Canada, the HFC and the average ratio of majority to minority members of Congress over the past two decades, an estimate of between 30 and 45 would seem reasonable for the House and 4 to 6 for the Senate.

Of the two chambers, the House should take priority. The Senate’s voting rules—requiring a super majority of 60 in many instances—and the usually more moderate stance of senators allows for a House focus. As well, the two-year terms and the more affordable campaign costs and manageable geographic boundaries of House seats offers greater and more realistic opportunities.

Above all, Green (Lite) candidates must be willing to play politics as it was meant to be played. This means a fundamental willingness to work across the divides with either or both majority parties as circumstances require.

— There are already too many Intransigent dogmatics in Congress. Adding to their numbers is not what this is about. —

This is not to say that candidates should be willing to sell their or their supporters’ souls for a few pieces of silver. It is to say that collaboration requires a penchant for compromise and an ability to know when enough is enough—or at least is as much as one is going to get at any particular time.

Green Lite candidates cannot be just about the environment and clean energy. Too narrow an agenda will fail to appeal to a broad enough constituency to win elections. The BC Greens and Senator Sanders should be looked to for the breadth of their issue agendas. Sanders’ substantial showing in the 2016 primaries was not just about character.

Sanders was believed a viable candidate—as opposed to simply an opposition candidate—for a variety of reasons including his addressing issues of health, education, employment, infrastructure and more. He suggested new, less dogmatic and more collaborative, ways of doing the people’s business. Our Revolution reflects Sanders’ broad campaign agenda.

Even after winning election, third party candidates will encounter obstacles—some significant– on their way to being a force to reckon with. The greatest of these may be securing committee positions. Congressional committee assignments are the purview of Republican and Democratic caucus leaders.

Senators Sanders and King now caucus with the Democrats. Sanders not only sits on the Senate Committees on Environment and Public Works and Veteran Affairs, he is the ranking (minority) member on the Senate Committee on the Budget and the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. King is the ranking (minority) member on the Water and Power Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, as well as a member of the Committees on Budget, Rules and Select Intelligence.

Independents have traditionally been permitted to participate with one or the other of the two parties in each chamber. This is done as a courtesy and there is no guarantee it would continue as the number of Green Lite members increases.

Logically, it would be foolish for either party to deny independent Green Lite members a seat at the table. Committee membership and participation in the seniority system would likely be made part of any partnership agreement.

Whether a Green (Lite) Party is the right path to pursue I can’t say. What I can say is that the status quo is untenable, from almost any perspective. An alternatives need to be pursued.

How long can the U.S. go on with a gridlocked Congress, relying on the courts to protect the environment from practices that threaten the health and welfare of the nation’s people and jeopardize Earth’s ability to support life as we know it?

The power of factions should not be under-estimated. The chances of a constructive internal changing of ways by either the Republican or the Democratic parties seems to me no greater than the odds of successfully establishing a Green Lite Party or other workable alternative.

A break with the current dysfunctional system can come about in one of two ways. It can either be a practical and measured evolution; or, it can be thrust upon us by circumstances gone out of control.

Should a Green (Lite) Party be tried? As our fearless commander-in-chief once said: what do you have to lose?

_______________

[i] [ Earth v Trump is not a real legal case. It is just my shamelessly subliminally plugging my forthcoming book of the same name.

[ii] Factionalism is here defined as more than a difference of opinion. Artless as this particular definition is it allows for distinguishing a faction by its unwillingness to accede to its own party’s core principles and positions.

Teaser Photo by Gary Bendig on Unsplash