After exploring the south of Scotland, from the East side to the West, I arrived to the Black Isle, a few miles away from Inverness, in the middle of the Highlands.

There, I met my new hosts Clive and Julie, a couple from London who had decided after almost two years of wwoofing in Northern Europe and in the UK to start a permaculture project of their own.

They bought a house with about 2.5 acres of land and woodland in August 2015, and since then have been working hard, designing and gardening.

They were hosting a workshop over the weekend, as part of the Grow North program, with the Black Isle Transition Network – who is doing a lot of great things in the area. We spent the first couple of days after my arrival building the structure for a big hugelbed, that would be filled by the participants with wood, compost, cardboards and leaves.

It was amazing seeing something coming out of the many pieces of wood I had collected in the forest and sawn, and I was really proud that nothing collapsed during the workshop! We also built a tattie bed out of old pallets, potted many tiny hazel trees, and constructed a small firepit out of old bricks. I had so much fun doing all of that, being outside and working on such great projects with lovely and motivated people.

The hugelbed

Some of the people at the workshop

I was also very impressed by how well-thought the whole project was. Julie and Clive have been working so hard on it, using permaculture principles to design a more sustainable life for themselves, through their garden and their behaviour. They are constantly imagining ways of being more self-sufficient, ecologically friendly and of having a low-impact. Their creativity, their openness and their kindness inspired me and made me feel very grateful of being able to do this project and stay with such interesting people. I cannot wait to see how their project will evolve in the years to come.

I tried to take advantage as much as I could of the beautiful Scottish sunshine to be outside and explore; but I also spent a lot of time reading on politics and green movements. I was really impressed by Murray Bookchin’s writings, a libertarian anarchist and founder of social ecology, whose work focuses heavily on our relationship to one another, which he describes as built on hierarchies; (What I called ‘privileges’ in my last article, and defined here as ‘not merely a social condition; it is also a state of consciousness, a sensibility toward phenomena at every level of personal and social experience’ (1)), and on our relationship to nature.

In the beginning of his book The Ecology of Freedom, written in 1982, he writes: “the very notion of the domination of nature by man stems from the very real domination of human by human.”

And that is why, according to him, “privatistic forms of spiritual self-regeneration’ and green capitalism have no weight compared to ‘economic growth, gender oppressions, and ethnic domination” in shaping our future (2).

Similarly, best-seller author and permaculture activist Starhawk states that ‘the struggle for social justice is an integral part of permaculture’ and that, ‘we can’t effectively care for ecological or human communities unless we address the structures of power that enforce destructive patterns’ (3).

Similarly, best-seller author and permaculture activist Starhawk states that ‘the struggle for social justice is an integral part of permaculture’ and that, ‘we can’t effectively care for ecological or human communities unless we address the structures of power that enforce destructive patterns’ (3).

In saying so, what is meant is not that individual examples and models of behaviours are unimportant or uninteresting, but rather that they are not the solution per se, and furthermore, that ‘ethical’ and ‘spiritual’ appeal can sometimes ‘obscure real power relationship by making the attainment of an ecological society seem merely a matter of “attitude”.

An ecological society cannot solely be based on a change of lifestyle (4), a notion also shared by Maddy Harland in some of her Permaculture Magazine editorials (5).

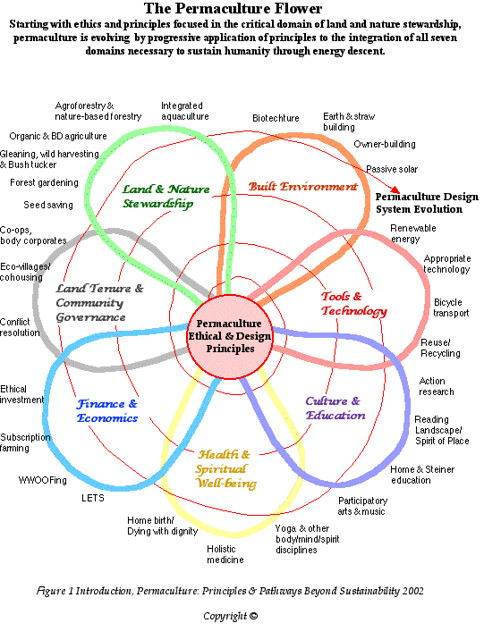

Bookchin therefore argues for direct democracy, urban decentralisation, self-sufficiency, self-empowerment, non-authoritarian and communal forms of social life. These ideas are recurrent in ecological movements and are often associated with the radical left, but are only very partly mentioned in Holmgren’s Permaculture Flower ‘Land Tenure and Community Governance’ petal (6).

By focusing solely on the ‘creating a better world’ part, and refusing, as a movement, to give a narrative of the systemic, structural reasons that led to this situation of near-collapse, I think the permaculture movement is undermining its potential.

To be perfectly clear, I would like to emphasise once again that this is not a criticism of sustainable lifestyle as such. I believe that the personal is very much political, and that what we chose to do with our body and our house and our wallet has a significant meaning that goes far beyond its immediate, individual repercussion; and it is something I try to apply in my every day life, through my diet, my consumer’s choices and my habits. Moreover, I also agree that social movements need people to ‘show the way’, be imaginative and utopians – I believe in the power of good examples and I have seen many through my journey.

What I am criticising is the representation, by the permaculture movement and mainstream media, of individual attitudes as the solution.

First of all, it gives the impression that individual, scattered initiatives are enough. That is why there are so many books on models of green living, and that positive initiatives frequently make the headlines – they give the audience what it wants, the feeling that the solution is already there, that it just needs to be developed. And it distracts our attention from other issues.

I read an article recently in a French journal about micro-farms – smallholdings using alternative agriculture such as permaculture – arguing that the latter were not the solution, because they gave the wrong idea that we could build a different model parallel to the one currently existing (industrial farming), without really having to deal with the problem of intensive farming (7).

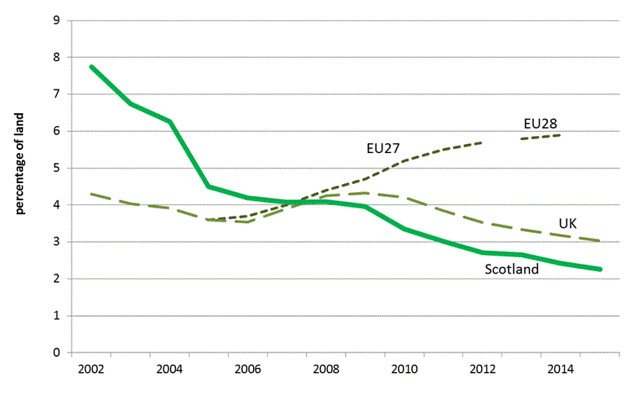

Our brains need positive information, and these initiatives are great sources of inspiration and of creativity. But let’s not forget to look at the big picture once in a while. A small reminder – in Scotland, smallholdings account for 2% of the land. 50% of the land is owned by 0.008% of the population, and as Craig Bayne highlights, ‘Scotland history is one of near-constant land theft’ (8).

This is a diagram that I found on the government website, that shows the percentage of land that are cultivated organically in Scotland compared to the rest of the EU. And it’s going down. Only 2.3 percent of agricultural land is cultivated organically (9). It is true that it doesn’t take into account the number of farms that are producing organic vegetables without the label (because it is very expensive and time-consuming), but it does show the general trend.

We must properly tackle issues such as land rights, common agricultural policy (which will change in the UK with Brexit – but we live in an interconnected world and what we produce and how on continental Europe will still have a large impact here), and industrial farming. It is not because we decide to only buy from local, organic farmers that these issues cease to exist.

The Black Isle

The Black Isle

We don’t want to create a sub-world for the few

Secondly, and it is something I have already mentioned in my previous article, permaculture is based on a strong voluntarist approach, with the underlying assumption that ‘if you really want to, you can do it’, highlighted in the very often heard ‘take responsibility for your own actions’.

If, like Holmgren, we focus on the new middle-class, then it is perfectly possible, because of the cultural, financial, networking heritage it usually confers, to do so. But home education is not possible if you are working full-time, if you didn’t yourself have any education, or if you don’t have the full financial support from a partner or family member. So I see two options there: either we build a sub-world for the few, a parallel model unattainable for the rest and therefore reinforcing inequalities; or it presupposes that we have had some serious, revolutionary society changes beforehand. When focusing all our time and energy on ‘creating a new world’, we need to make sure it is a world in which everyone can take part of.

Now, permaculture has the potential to do so. Starhawk’s ‘Earth Activist Training’ directly confronts the necessity for inclusivity, diversity and social justice. Maddy Harland’s editorials usually call for a more political stance. Graham Burnett’s radical permaculture views, mingled with anarchism and veganism, are also very political. Groups such as the Black Permaculture Network link permaculture principes to the Black Panther Party ’10-point program’. Places like The Grange, in Norfolk welcome refugees, asylum seekers and are fully developing the concept of resilience.

Permaculture is a fantastic tool of self-empowerment, and has the potential to be used in subversive, radical ways, and to truly change the status quo. As a movement, as a community, let’s collectively embrace those issues, let’s make sure they are at the core of our actions, let’s be angry because we live in an ecologically, socially unacceptable world and let’s have hope because we can change it!

For more information on Clive and Julie’s project, visit their facebook page: www.facebook.com/BlackIslePermacultureArts

If you want to learn more about Transition Black Isle, its here: www.transitionblackisle.org

Sources and Further Reading

As this is a blog article and not a research article, I took some liberties with the presentation of footnotes. Please contact me if you would like further information on my sources.

(1)Murray Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom, 1982

(2) Ibid

(3) Starhawk, ‘Why Diversity is Important in Permaculture’, in Permaculture Magazine, Winter 2016

(4) Murray Bookchin, ‘What is Social Ecology’, in Environmental Philosophy: From Animal Rights to Radical Ecology, 1993

(5) Maddy Harland, ‘Editorial’, Permaculture Magazine, Autum 2016

(6) David Holmgren, Permaculture. Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability, 2002

(7) http://revue-sesame-inra.fr/microfermes-on-perd-une-energie-folle

(8) Craig Bayne, ‘Yes to Land Reform’, The Land, 2016

(9) www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Agriculture-Fisheries/TrendOrganicFarming

Additional websites

http://blackpermaculturenetwork.org/solidarity-statement

https://kpfa.org/program/against-the-grain

https://earthactivisttraining.org

http://thegrangenorfolk.org.uk/index.php/blog

More information about Graham Burnett: www.permaculture.org.uk/user/graham-burnett

https://permaculturenews.org/2009/02/19/rediscovering-democracy

http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bookchin/socecol.html

www.filmsforaction.org/articles/reflections-on-castoriadis-and-bookchin