The environmental movement has struggled, at least until recently, to see human settlement as part of a natural system. The environmentalism that I grew up with largely treated humanity as THE problem that needed to be overcome. Wherever humans are, nature is diminished, ergo an approach that sought to limit human presence. I never could align with the environmental movement, not even in a small way, even though I think we could agree on many things, largely because I saw the byproduct of environmental activism as bad development.

If a development was proposed at five units per acre, the local environmentalists would advocate for no development, but would settle for two units per acre. If the proposal was two units per acre, they would push for one. If the strip mall had six units, they would push for three and then settle on four if they could get native plants in the stormwater retention area. And don’t laugh – I’m not joking. I saw that exact scenario play out many times.

The dangerous legacy of this thinking is the notion that better rules, regulations and process are the proper response to bad outcomes. Right now our rules are producing bad outcomes and so we need to get all hands on deck to fight and change the system so we have better rules. Of course, what is always lacking here is an appreciation for the fact that the bad rules we are trying to replace today were put in place by people trying to fix things in the past. Our solutions inevitably create our next problem, a process that has gone on all throughout human history.

Only now is different because we are creating and solving problems at such an enormous scale. We have the money, desire and centralized power to “right” the world in our image, whether that be environmental policy here at home or nation-building at the point of a gun abroad. Make no small plans.

Only we lose – rather ironically and tragically, in my opinion – the very thing that the environmental movement seems to worship: the wisdom of natural systems.

We shouldn’t pump CO2 into the air because we’ll mess up the natural climate cycle. We shouldn’t drain or even modify wetlands because we upset the natural ecosystem. We shouldn’t harvest all the cod, shoot all the wolves or even kill all the mosquitos because they are part of this larger natural ecosystem.

I’m with the environmentalists on these things, but for different reasons. I look at these complex systems and, with great humility, acknowledge that the complexity exceeds my ability to fully understand. In the face of uncertainty, I would stick with what we know works. I would, to the greatest extent possible, limit how much we impact these natural systems.

Now some of you environmentalists may agree with that, but most of you are going to cite statistics for how much the temperature is going to change over the next fifty years, how many whales will die, how forests will change and how many hurricanes we will have. These are all based on models, models which environmentalists express untold confidence in.

There is the paradox. If the wisdom of complex natural systems is understandable by humanity, then it can be manipulated and optimized by humanity.

I believe that this wisdom can never be fully understood – it is self-emergent with infinite complexity – but that our hubris in thinking it can be causes us to do all kinds of destructive things (largely in the pursuit of “good”). And it ultimately moves our debate over growth and development into areas that are irrelevant to building a strong town.

Last week I had a documentary film crew follow me around. They would record what I did, my conversations, the Curbside Chats and workshops I did and then we also did a couple of interviews. At one point they asked me to summarize the difference between pre-Depression and post-War development. Here was my summary:

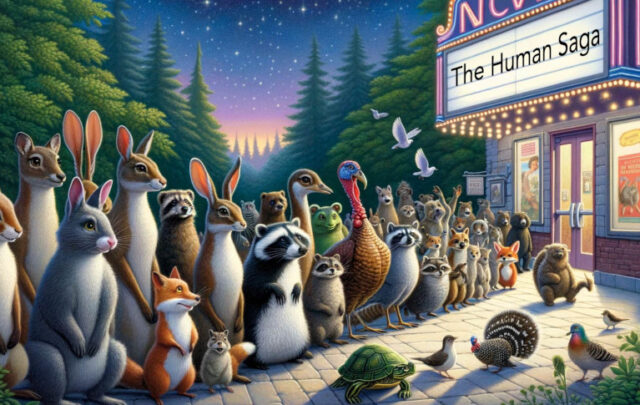

Rainforest is to corn field what traditional city is to post-war development.

The environmental movement can appreciate that a rain forest is a complex, natural environment. It is self-emergent and self-optimized. Each tree, each plant, has its own fractal ecosystem that combines in infinitely complex ways to create the rain forest. When a tree dies, it feeds new growth all around it. This is incredibly resilient and adaptable.

When we cut down a rain forest and plant a corn field in its place, we optimize for growth and efficiency, but that is it. A bad rain, some cold weather, a little bit of drought and our corn field is done for. We eradicate pests and anything that would impede the growth and efficiency of corn production, but we can’t decide halfway through the growing season that beans would be more valuable than corn.

Here’s the leap for those of you who see humans as THE problem, with the solution to this problem being centralized regulation to achieve your optimum set of outcomes: Cities were built for thousands of years in the same natural, emergent way that rain forests were. Humans, in very complex interactions, came together and built places. Each neighborhood, each block, had its own fractal set of constructs – social, political, financial – that combined in infinitely complex ways to create a city. Like any natural system, it was often messy and difficult at the fine scale. That messiness was required, however, because it took that continuous, low-level pressure and stress to optimize the system, just as happens with a rain forest. Again, incredibly resilient and adaptable.

We, of course, have destroyed the traditional way of building cities. In our attempt to optimize for growth and jobs, we’ve given cities all the fragility of a cornfield ecosystem. One small housing slowdown and cities start to fail. Gas prices go over $4.50 a gallon back in 2008 and budgets implode. We’re still not anywhere near meeting our maintenance and pension obligations and we’ve had over four years of positive economic growth. We’re literally so tightly optimized for one or two outcomes that most of our cities can’t take a punch.

The same goes for our centralized economy, which today is a dangerous combination of trickle down corporatism and trickle down government.

If we want to build strong towns, we don’t need a new form of the centralized approach, a new variant of the current theme. We don’t seek a different code of centralized regulations or a different set of centralized spending priorities. What America needs is a different system that begins on the block level and builds from there. It is far beyond simply “going local” but instead is a full embrace of the proven wisdom of complex, self-emergent systems.